🇭🇹 Can soccer save Haiti? James Louis-Charles believes so

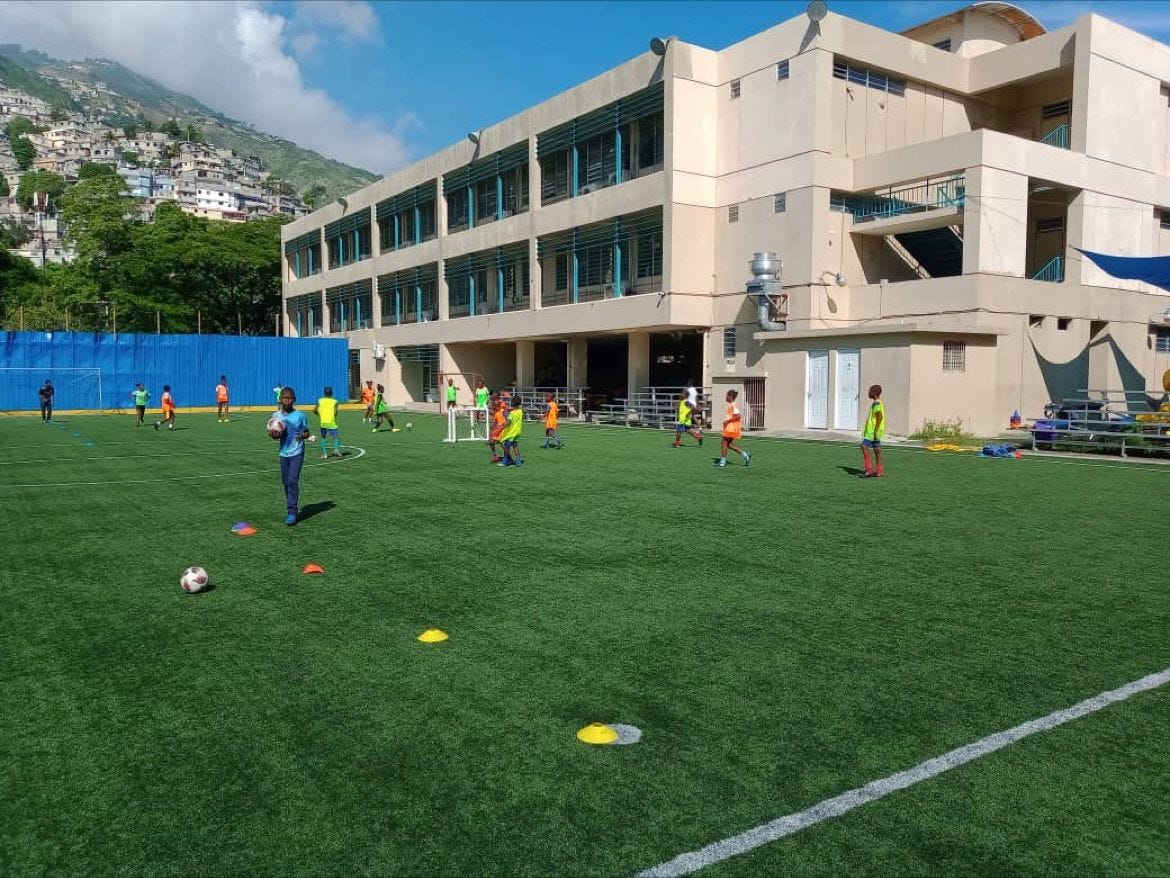

FC Juvenat provides hope amidst a crisis that many don't believe can be solved.

James Louis-Charles sighs and navigates his car toward another checkpoint. His path to the school where he teaches is obstructed by men. Those men are wearing masks. Those men are toting guns. What used to be a 10- or 15-minute commute sometimes involves as many as four checkpoints. That the sight is familiar and that this is now part of his routine does little to settle his nerves since he never knows who is behind the mask today … or what they might do with those guns.

“You don’t know if they’re police, you don’t know if they’re gangs. You just don’t know,” Louis-Charles said. “So, you take that risk on a daily basis just to get to school.”

This is daily life in Haiti, a country that has been struggling for some time but that has only seen its problems deepen after the 2010 earthquake and, more recently, the 2021 assassination of president Jovenel Moïse. The assassination created a power vacuum filled by gangs.

Even so, Louis-Charles presses on. He is the director of FC Juvenat, an academy he founded in 2023 that works to both give children the necessary training to pursue a career in elite soccer and gives them a safe place to play.

When the FC Juvenat kids are on the field, working on typical drills - and getting proper food and hydration, which has become a challenge as inflation in Haiti continues to rise since gangs control ports and regularly hijack trucks carrying food - Louis-Charles sees happiness on their faces.

The idea is the same as an academy in the U.S. or Europe: Produce top soccer players and give them a pathway to become professionals. There are tryouts and the number of children he can accept in the program is limited. But for FC Juvenat, there are other key goals as well.

“We don’t only allow them a place to play soccer,” Louis-Charles said. “We train on leadership skills, on conflict resolution. There’s a big emphasis on letting girls play because in the capital with the gang situation you hardly see girls playing soccer because it’s a big safety concern for girls and women to walk the streets of Port-au-Prince.”

With the checkpoints, kidnappings and extortion, the danger for women, the struggle to find reasonably priced food, and the general anxiety of day-to-day life, sports lose significance. And in Haiti, sports means soccer.

“We go crazy for soccer. When countries like Brazil or Argentina are playing, the country stops. You would think you were in Brazil!” Louis-Charles said. “When Haiti is playing, they don’t have the same motivation because they don’t see themselves as being those players.”

It doesn’t help that the men’s national team hasn’t been able to host a match on home soil since a June 2021 World Cup qualification contest against Canada. That game shouldn’t have been hosted in Port-au-Prince, either. During a qualifier three months earlier, Belize’s bus was stopped and held by armed men. Eventually, their release was negotiated, but at the time a member of the Belize delegation told me the team was, understandably, rattled.

Even as the women’s national team has reached new heights, qualifying for a first-ever World Cup, they haven’t played at home since 2019.

Right now, neither team could play at the national stadium even if they wanted to. It was taken over by gang members in late February, with the Haitian federation putting out a statement in March condemning the vandalism that took place.

The latest news on social media regarding the facility were reports of a shooting, with three killed when gunmen shot at a school bus in front of the stadium. The men’s league has resumed, playing a modified calendar that mostly includes teams from outside the capital.

With so many difficult moments taking place in Haiti and so little of the world’s attention seemingly focused on helping the country out of its crisis (and, to be fair, the world doing a pretty horrible job of helping the country at any point in the past), why does Louis-Charles still carry on running his soccer program and advocating for the country’s future?

Unlike the conflicts in Gaza or Ukraine, Louis-Charles says, Haiti’s problems are ones that could be solved without military intervention.

Most young boys don’t dream of becoming a gang member, but what choice do they have?

“The situation in Haiti is a socio-economic situation where there’s no jobs, there’s nothing for these kids and Haiti has the youngest population in the whole region,” he said.

But ever since it won its independence from France and became the first republic founded after a successful slave rebellion, its former colonial masters worked to keep it in debt.

The international community now says it is aligned and working for the good of Haiti, helping to install a transitional government and with a Kenya-led police force set to arrive and try to take control of the country back from the gangs (though that arrival has been delayed).

In addition to a serious level of economic investment, “I honestly believe it can be resolved through sports,” Louis-Charles said. “If there’s a solution, and this is what I’m trying to convince people of, is whatever solution that’s proposed to Haiti if you create a pathway, sports leagues, a system like the United States with basketball or Brazil with soccer, sports has been an avenue for underprivileged kids to reach their dreams.”

Some of that confidence comes from his own experience. After moving to the U.S. during high school, Louis-Charles was able to join an academy and play in college. After earning his Master’s in Sustainable Peace through Sports, he got a job back in Haiti working with an organization in Léogâne, near the epicenter of the 2010 earthquake.

There, he served as the director of a program with more than 400 children, some of whom later earned call-ups to youth national teams. He lived in the capital and commuted to the west but left that job after the gang surge led to a number of firefights along his route.

After accepting a teaching and athletics director job with another school, he realized the appetite was immense for a program that not only would allow kids to play soccer but also for a way to give kids something to consider as a career after they turn 18.

While Juvenat is relatively stable compared with neighboring communities, there still are risks. The program was paused in the spring before successfully restarting two weekends ago.

That return, which Louis-Charles decided to undertake after hearing from many kids about FC Juvenat training being the highlight of their weeks, is one of few positive stories coming out of Haiti right now. Despite the difficulties and the uncertainty, he already wants to lay the groundwork for the next step when it’s possible to take it.

“Once everything is back to normal we do plan on expanding the program to a few other schools.

“So it's a question of, again, waiting for this to get back to somewhat normalcy, so that we can continue on with our program,” Louis-Charles said. “The long-term goal is to open an academy and to establish relationships with soccer clubs, whether it's MLS or European soccer clubs, because, I truly believe we have the talent in Haiti, and those kids also should have the right to dream, you know?”

For now, it just isn’t clear when the men with guns will abandon their checkpoints, when the country will again have a head of state and when that normalcy will arrive.

If you’d like to donate to FC Juvenat, you can do so at this GoFundMe

Tomorrow I’ll preview the Liga MX final. Subscribe to get that in your inbox!

That you're covering Haiti at all is a testament to your good work. There are so many important stories to tell and Louis-Charles' is such a positive one. I really enjoyed this piece

Thank you for sharing our story! It's great!

Mesi anpil!